Cruisezillas in Paradise: The Environmental Reckoning of Samaná’s New Cruise Terminal

As the Dominican Republic proudly prepares to cut the ribbon on the new cruise terminal in Samaná Bay, there’s a sense of déjà vu I can’t ignore.

I’ve seen this story before – in Bali, Tulum, Cancun, Las Terrenas, and elsewhere. What begins with the promise of prosperity ends in traffic jams, sewage runoff, and a devastated coastline. So before we start popping the champagne and printing “Welcome Aboard” banners, let’s talk about what this terminal really means.

The Tricky Economy of Cruise Tourism

It’s easy to get dazzled by the numbers: “thousands of passengers per ship,” “millions in port fees,” “jobs for locals.” But let’s unpack that.

Studies show that cruise passengers spend just $70-$100 per day onshore – often less in isolated ports where the cruise lines own the terminals, shops, or offer exclusive excursions. In contrast, eco-tourists or independent travelers often spend 3–5x more and stay longer, spreading their dollars across local hotels, restaurants, guides, and transport services.

What’s worse? Most cruise tourism revenue leaves the country. Ships are registered under “flags of convenience” (Panama, Bahamas, Malta) to dodge taxes and labor laws. Onboard staff are often outsourced and underpaid. And ports? Many are developed through public-private partnerships where the risk is public, and profit is private.

Take Labadee, Haiti. It’s a fenced-off private beach leased by Royal Caribbean for 99 years. Local Haitians can’t enter. The economic benefit to Haiti? Pennies on the dollar.

Samaná Bay: What’s At Stake

This isn’t just any bay. Samaná Bay is one of the most biodiverse marine ecosystems in the Caribbean. Every winter, up to 1,500 North Atlantic humpback whales migrate here to breed and calve – one of the last places on Earth where this happens in such visible numbers. Whale-watching in Samaná is already a $20M/year industry – sustainable, community-driven, and low-impact.

But these giants of the sea rely on calm, undisturbed waters. Cruise ship noise (underwater decibels over 170 dB) interferes with their communication and navigation. Ship collisions with whales are not rare—globally, at least 100 endangered whales die from such strikes each year, often unreported.

And it’s not just whales.

- Coral reefs, already under stress from climate change, bleaching, and sedimentation, are sensitive to the turbulence created by large ships. Sediment stirred up by propellers can smother coral polyps and reduce sunlight penetration by up to 60%.

- Mangroves, nature’s coastal filtration system and fish nurseries, are often bulldozed for port infrastructure or contaminated by oil discharge and bilge water.

-

Fisheries decline due to habitat degradation and contamination – threatening local food security and livelihoods.

Cruise Ships: Floating Cities with a Dirty Secret

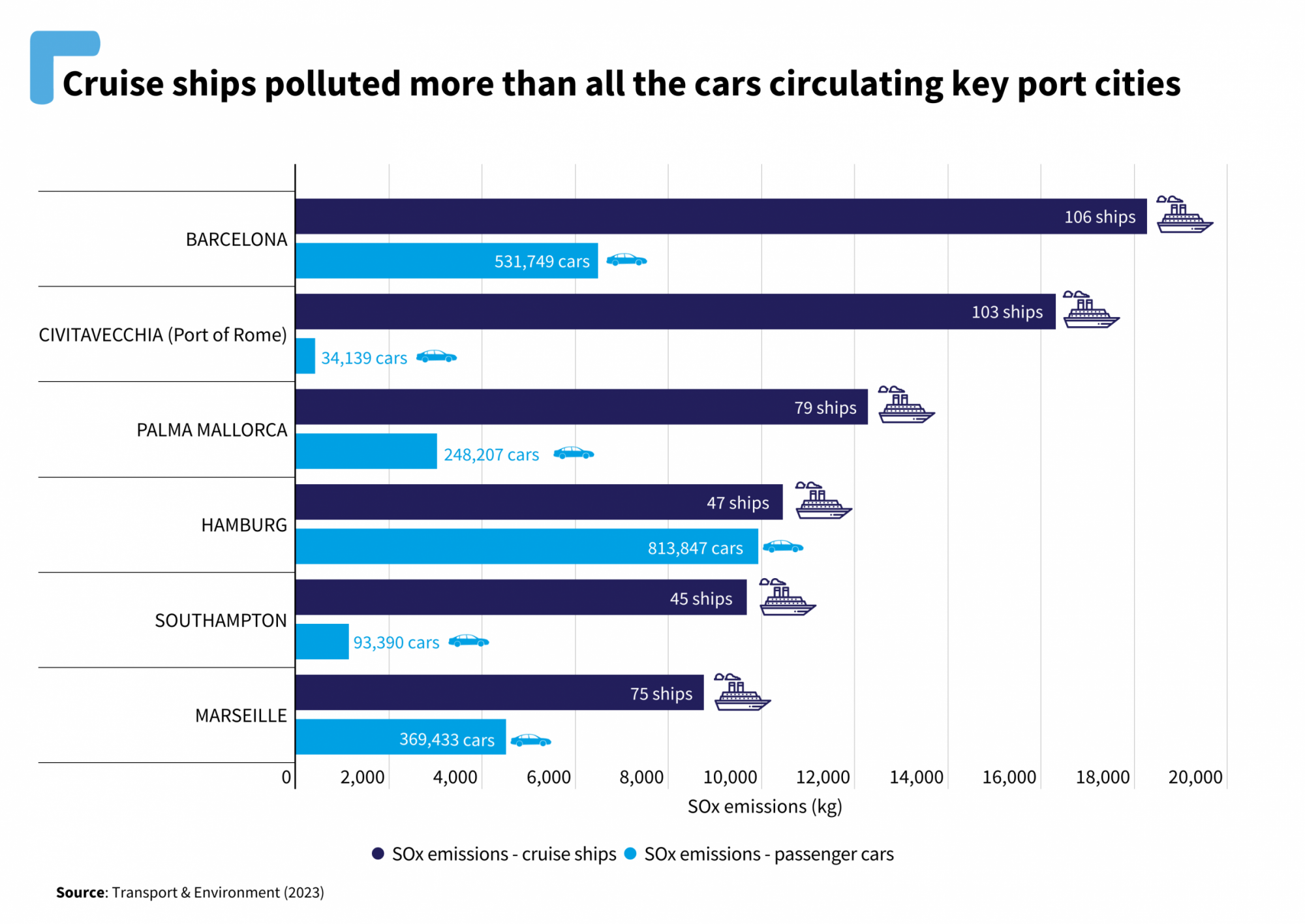

Let’s not mince words: cruise ships are among the dirtiest forms of travel on the planet. A single mid-size cruise ship can:

- Emit as much sulfur dioxide as 13 million cars per day when burning heavy fuel oil.

- Generate 210,000 gallons of sewage, 1 million gallons of gray water, and 8 tons of solid waste per week.

- Release ballast water that introduces invasive species into fragile ecosystems.

Global fleet statistics from pre-pandemic years show that the industry carried 30 million passengers annually, producing over 1 billion gallons of black water and almost 5 billion gallons of gray water. Even under new regulations, cruise lines routinely violate discharge rules. Between 2010 and 2020, one major cruise line was fined over $60 million for repeated illegal dumping and falsifying records.

Let’s call this what it is: industrial tourism.

Case Studies: Cautionary Tales from Paradise Lost

- Venice, Italy: Faced irreversible damage to its historic architecture and lagoon from cruise ship waves and pollution. In 2021, banned large ships from entering the city center. Too little, too late?

- Cozumel, Mexico: Now the busiest cruise port in the Caribbean. Coral reef degradation exceeds 50% in some areas. Locals report a “hollow economy” with mass tourism but few long-term benefits.

- Bar Harbor, Maine (USA): Imposed daily cruise passenger caps after locals complained of congestion, housing inflation, and environmental stress.

- Georgetown, Cayman Islands: Shelved plans for a mega cruise port after a nationwide referendum and marine biologist outcry over the destruction of 15 acres of coral.

Why are we so eager to repeat these mistakes?

The Samaná Opportunity: A Different Story

Here’s the thing. I’m not against tourism. I live here. I love it. I want people to experience the magic of Samaná.

But I am against lazy, copy-paste, short-term development thinking.

We need a model that respects:

- Environmental Limits – Recognize that Samaná’s ecosystem is its main economic asset. Destroy that, and the game is over.

- Local Value Capture – Make sure tourism dollars stay in the hands of locals, not offshore conglomerates.

- Slow Tourism – Attract travelers who care, stay longer, and give back more than they take.

- Community Consent – Engage the people who will live with the consequences long after the ribbon is cut.

Final Thoughts: Will Samaná Be Another Victim or a Global Example?

If we sleepwalk into this future, Samaná could become yet another beautiful place ruined by greed, greenwashing, and bad planning.

But it doesn’t have to be.

We still have a window – narrow but real – to create a blueprint for sustainable cruise tourism. One where visitors are welcome, but nature is sacred. Where profit doesn’t come at the expense of the people who live here. Where we can look our kids in the eye and say: “We built something better.”

This is a test.

Let’s not fail it.

The first step? See how we’re working to protect Samaná from commercialization, overdevelopment, and mass tourism through the region’s first Community Land Trust.

Marek Zmysłowski